Homer Fellows Kept The City Rolling with Springfield Wagon Company

Moving isn’t an easy task, but we’re lucky to have plenty of ways to make it a little simpler: moving vans, trucks, dollies and plenty more. In 1873, however, this wasn’t the case. Wagons were the most efficient manner of transporting materials so our communities could grow and expand further than previous boundaries.

The Springfield Wagon Company, established by Homer Fellows, was one of the premier wagon companies of its time. Not only did the company see great success, it helped put Springfield on the map as one of the best sources for wagons.

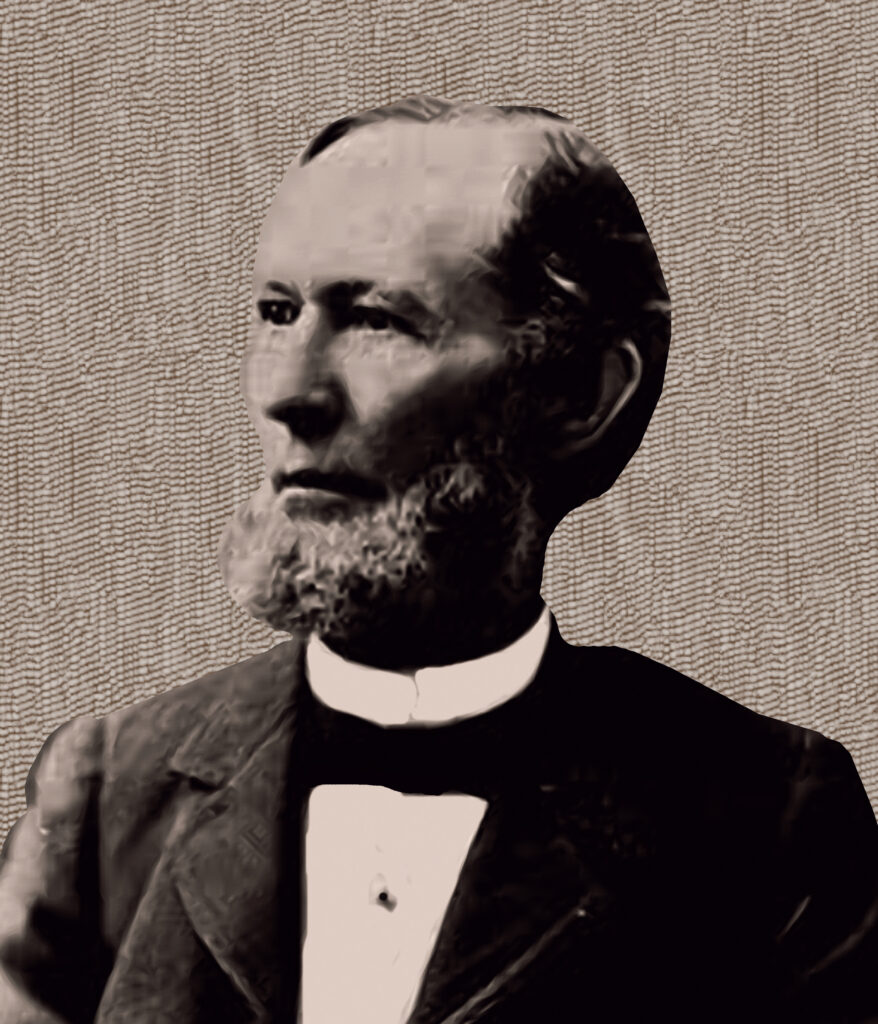

Fellow’s Life

Homer Fellows was born in Wellsboro, Pennsylvania in 1832. When he was around 21, he relocated to Iowa to work with a mercantile company. He began as a salesman and then moved his way up through the company. In 1857 he worked with two individuals to establish real estate offices in Warsaw, Missouri and Springfield, Missouri. During this time Fellows also worked with other stockholders to establish the first telegraph line through Springfield.

Fellows’ life was never one of monotony. In 1861, he went to the District of Columbia and was appointed register of lands for the Springfield district by President Lincoln. A year later, he chose to join the military during the Civil War. Fellows was appointed as Lieutenant Colonel of the 46th Missouri Militia. He served for one year.

Springfield Wagon Company

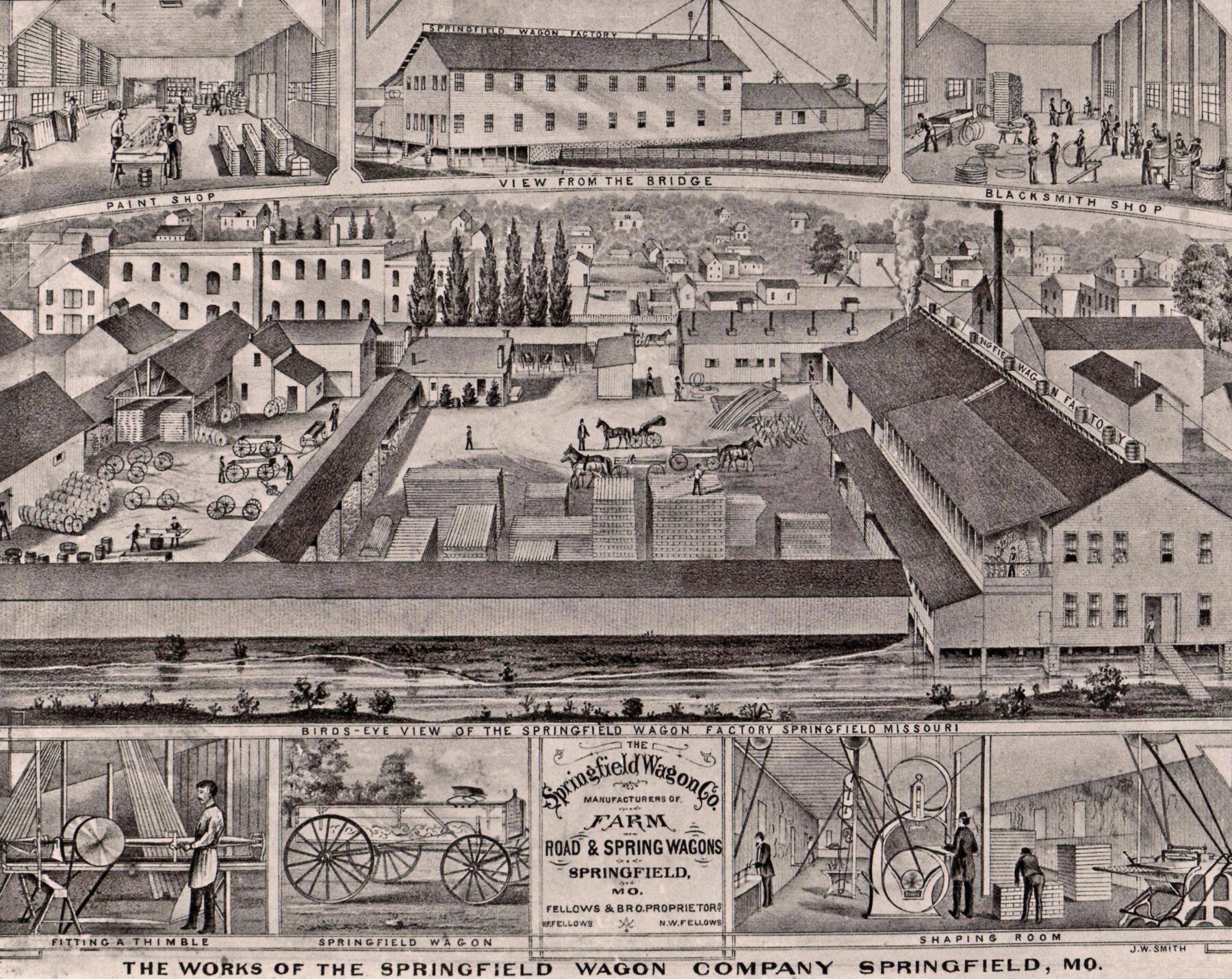

In 1872, Fellows would find a new job as secretary and factory superintendent of the newly incorporated Springfield Manufacturing Company. He designed and built the first wagon that the company ever created with a hinged drop-tongue to make it easier to navigate the wild Ozark hills and roads.

The economic disaster known as the Panic of 1873 forced the company into near bankruptcy and stockholders were eager to sell the company. In 1875, Fellows reorganized the business as the Springfield Wagon Company with himself as the president and principal stockholder.

The company saw great success even during an economic downturn. The farming land around southwest Missouri and northwest Arkansas necessitated the purchase and use of wagons, even if the economy was poor. Due to being the endpoint of a major railroad, the city also saw cheaper freight rates on raw materials and finished products, giving the company a financial advantage when it came to building wagons.

The wagons themselves were a great point of pride for the company and were considered a good, durable investment. One historical record describes a Springfield Wagon Company wagon as, “…built by master wagon-makers equipped with precision tools and dressed in its bright green and yellow paint, it was a work of grace and beauty. It was light of weight, easy of draft, yet sturdy in construction.”

Not only did they believe they were the best wagon out there, Springfield Wagon Company was determined to prove it as well. In 1876 the company advertised in newspapers that their wagon was the strongest and lightest one on the market and that they would be willing to have a judge determine the best. Studebaker Wagon Company agreed, and the contest date was set for the end of March with the loser agreeing to donate $500 to Drury College. Studebaker Wagon Company never showed up to the challenge, making Springfield Wagon Company the winner by default.

In 1883 disaster struck when a defective drying kiln started a massive fire that destroyed their plant. That didn’t hold back Fellows, though, and the company was able to be back in business by 1885.

The company’s persistence paid off in 1886 when the Springfield Wagon Company wagon was chosen as the “best two-horse wagon” at the Fort Smith Arkansas Fair. This award allowed them to charge more for their wagons, significantly increasing their profits. Instead of pocketing the difference, Fellows instead cut the workers’ 10 hour days to 8 hour days while still paying them as though they had worked 10 hours. Their success continued and by October 1877 the company was building 75 wagons a week. By 1893 the company had produced over 3,500 wagons.

After Fellow’s Death

In 1894, after living nearly 50 years in Springfield, Homer Fellows died, leaving the company in the care of Charles McCann. McCann was president of the company for five years until Homer’s son, Frank Fellows, took over the company. Frank helped the company continue to prosper even after the loss of his father.

The company faced a major threat in 1905 when the International Harvester company organized and began offering installment plans for their wagons and trailers. Fellows was able to find a solution by asking his banker friends to assist with setting up payments for those who purchased his wagons.

Frank Fellows also helped establish Springfield Wagon Company as the brand for fairs, circuses, and carnivals. These events required heavy animal cages with wide-tired vehicles, and Springfield Wagon Company was happy to oblige with their needs. Some of their major customers included famous companies Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey, The Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Show, and more.

The company carried a virtual monopoly on wood wagons as the market decreased around 1925. With the decreasing need for wooden wagons, the company began to break into making steel farm wagons and highway trailers, allowing them to keep up with business and remain open during the Great Depression.

Springfield Wagon Company was sold to Phipps Lumber Company in 1941 and was then relocated to Fayetteville, Arkansas. The company continued there until 1951, when lack of demand meant the end of production.

To learn more about the Springfield Wagon Company, visit us at the History Museum on the Square. Not only can you read about the company, you can get an up-close look at a wagon that was donated to the museum.