The Story of Fred Coker, Horace Duncan, and Will Allen – 1906 Lynching

Current Setting

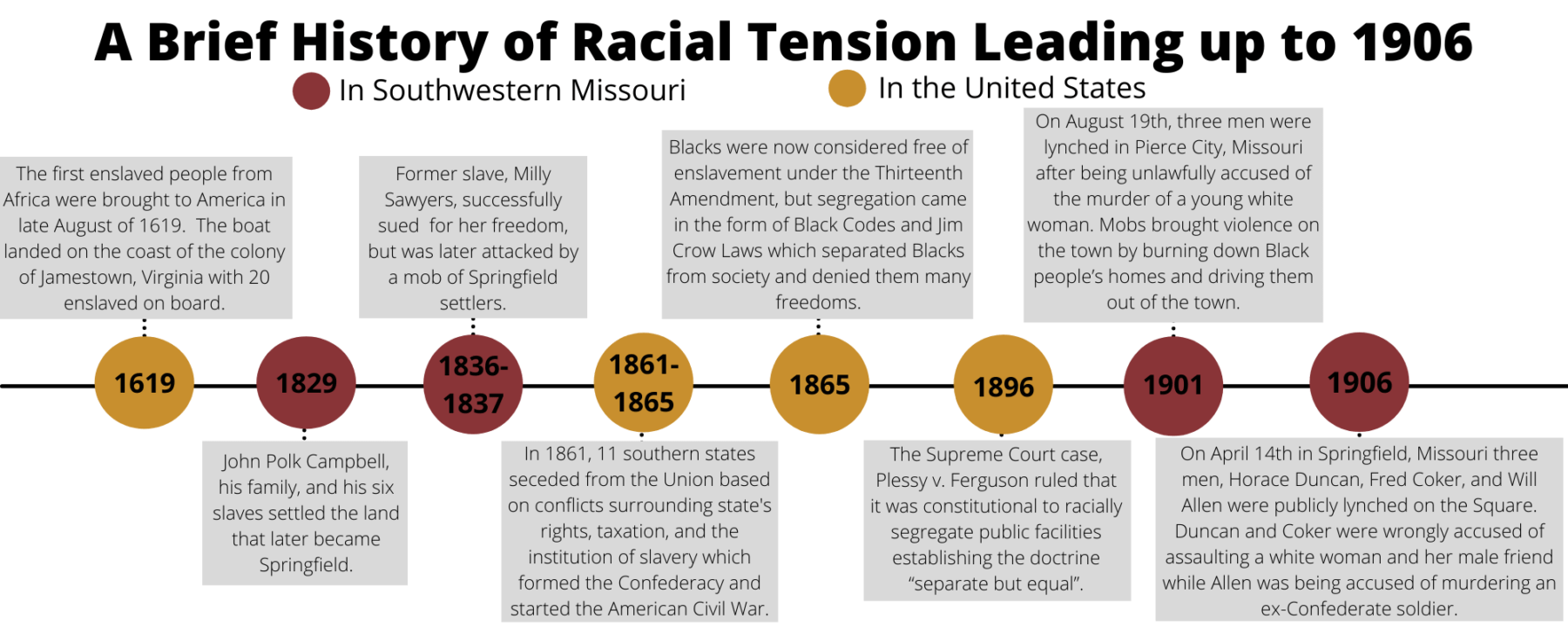

Just as there is with every town, Springfield has both great and unsavory aspects of its history. On Saturday, April 14, 1906, three innocent men, Fred Coker, Horace Duncan, and Will Allen were brutally murdered and hanged in Springfield’s public square. This is the same public square that the History Museum on the Square sits near today. In the days following the Civil War, racial tensions in Missouri grew rampant as the societal roles of Blacks came into question. The state had an interesting position in the Civil War as it belonged to the Union, but still allowed slavery, thus carrying both Southern and Northern sensibilities. Post-Civil War, Missouri abided by Jim Crow practices, which socially separated Blacks from Whites. While these types of racial tension existed in Springfield, the city’s Black citizens played an important role in the community. Many of the businesses were Black-owned and were both successful and patronized by a variety of Springfieldians.

Violence against Blacks in Springfield was unfortunately common at the time and there may have been several occurrences that acted as a catalyst towards this specific murder. On the other hand, some Whites saw the importance of integrating black people into society and fought towards that goal.

Friday, April 13, 1906

Several events stirred violent behavior against Blacks in Springfield, but there is one event in particular that directly resulted in the lynching of Fred Coker, Horace Duncan, and Will Allen. On Friday, April 13, 1906, Mrs. Edwards, a white woman, (whose first name has been recorded as either Mina or Mabel, depending on the source) went into Springfield for the day and, that evening, met up with her white friend, Charles Cooper. They visited a brothel on the Northwest side of town, but the details of the story are unclear of what happened after they left. The next morning, Saturday, April 14, local newspaper, the Republican, printed a story suggesting that there was an assault upon Mrs. Edwards the night prior, done by two Black men. Cooper claimed that he had been robbed and knocked unconscious during the event. After the assault, Mrs. Edwards was supposedly taken to the home of police officer John Wimberly and was reported to be in serious condition. However, Mrs. Edwards was a woman known for her dubious reputation and previous claims of assault were consistently determined to be false.

Saturday, April 14, 1906

Action was taken immediately regarding the alleged assault that Saturday morning regarding the alleged attack, leading to the arrest of 20-year old Horace Duncan and 21-year-old Fred Coker. Duncan lived with his widowed mother and his father had been a blacksmith for the Springfield Wagon Factory. Coker was raised by his grandfather, King Coker, who was a respected Black leader. Duncan and Coker were known to be hardworking and responsible individuals and their white employer, Tom Morrow, provided an alibi for them stating that they were working during the time the crime was taking place. Despite having a solid alibi, Coker and Duncan were booked for robbery at the county jail, but not for the alleged assault.

The newspaper story caused rumors to spread throughout Springfield riling up its citizens. Sheriff Everett Horner had been in charge of the county jail that evening and had heard of several possibilities of violence in the city. Horner sent deputies to the streets to investigate, but they reported that nothing was amiss. By 8pm, a large crowd of about 3,000 men and boys had formed on the square and was heading towards the city jail. The mob discovered Duncan and Coker were not being housed at the city jail, and changed route up Booneville Hill towards the county jail. With great determination, they broke into the jail using a telephone pole and items they looted from Frisco shops and several black smith shops to batter down the county jail door. As the mob entered the jail, Sheriff Horner and his seven deputies did little to protect the inmates and even identified Coker and Duncan for them. The men broke into the cell, forcefully removed Coker and Duncan and dragged them from the county jail on Booneville all the way to the public square; the men pleaded their innocence the whole way. The public square held the Gottfried Tower where the mob took the lives of Coker and Duncan by hanging them from its balcony and burning their bodies. The mob’s violent hunger was not yet satiated, and they returned to the county jail to claim another victim, Will Allen, who was a suspect in the murder of old Confederate soldier Roark. Once they brought Allen to the square, they gave him a mock trial before he met the same inevitable fate as Coker and Duncan.

Sunday, April 15, 1906 – Easter Sunday

The tragedy that befell the town had citizens divided. On the next day, Easter Sunday, there was talk of people threatening to burn down the Black district and drive Blacks out of the town as had been done in other towns in the area. The reality of the three men’s violent murder and the continued threat towards Black people in the community, sent many Black people to pack their bags and leave Springfield for good. The destruction and violence brought in officials and state militia from Pierce City and Aurora, who stayed in Springfield for 10 days to protect the Black district and its people that were being threatened.

When it came to charging the assailants, the county prosecutor and the judge of the criminal court were determined to convict every guilty party that took part in the lynching. There were even charges filed against the Springfield police for negligence based on their lack of involvement in stopping the mob. In a Grand Jury trial, they confirmed that the lynching was both unjustifiable and unlawful. Unfortunately, the people who murdered Fred Coker, Horace Duncan, and Will Allen were never brought to justice as the jury chose not to convict the only person tried for the crime. This event strongly influenced the future of Springfield and even caused greater segregation in the community further isolating Blacks. Today, we commemorate the heinous event with an historic marker erected in 2019 in partnership with the Equal Justice Initiative. It resides on the Northeast corner of Park Central Square, close to where the Gottfried Tower once stood.

What is Next?

In April of 1906, the dynamic of the city of Springfield was significantly changed to a point that continues to shape our community even to this day. On the night of April 14, going into the early hours of April 15, three Black men, Fred Coker, Horace Duncan, and Will Allen were wrongly accused of crimes that led to their untimely demise as they were brutally lynched in the Springfield square. While this was, unfortunately, not the first lynching to occur in the area, the impact was insurmountable. Many Black families left Springfield for good as they saw racial tensions rise and their safety become more and more at jeopardy. Understanding horrific stories, just like this one, is important towards continued growth as a community.

Get Involved – Donate to our Cause

As the History Museum on the Square continues to develop and grow as an institution, we acknowledge that our exhibits will develop with us. We are currently working to add information to our permanent exhibits regarding the 1906 lynching that happened on our city square. This story, while tragic, must be told and the lost lives of Fred Coker, Horace Duncan, and Will Allen must be recognized. Donations toward this project will be put in a restricted fund that will be used to install an exhibit regarding the 1906 lynching and continue the museum’s efforts to bring to light more of our community’s diverse stories.

Continue your research on local Black history and initiatives that fight racial inequality with these websites:

African American Heritage Trail Springfield

Katherine Lederer Ozarks African American History Collection at Missouri State University

Digital Photo Archives at the History Museum on the Square

Written by Ashley McLaughlin