Wild Bill Hickok: Bringing the Dueling Wild West to Springfield, Missouri

Springfield, Missouri, is known for many things: cashew chicken, our ever-changing weather, and the Birthplace of Route 66. Thanks to Wild Bill Hickok, Springfield got to add another feature to that list: the origin of the quick shooting duels that are a hallmark of western movies. An argument over a pocket watch and two men drawing their pistols led to a bloody end on what is now Park Central Square, a showdown that was captured in films for decades after. The life of Wild Bill Hickok tells a story that embodies the image of the wild west with ties to our own Springfield, Missouri.

Who Was Wild Bill?

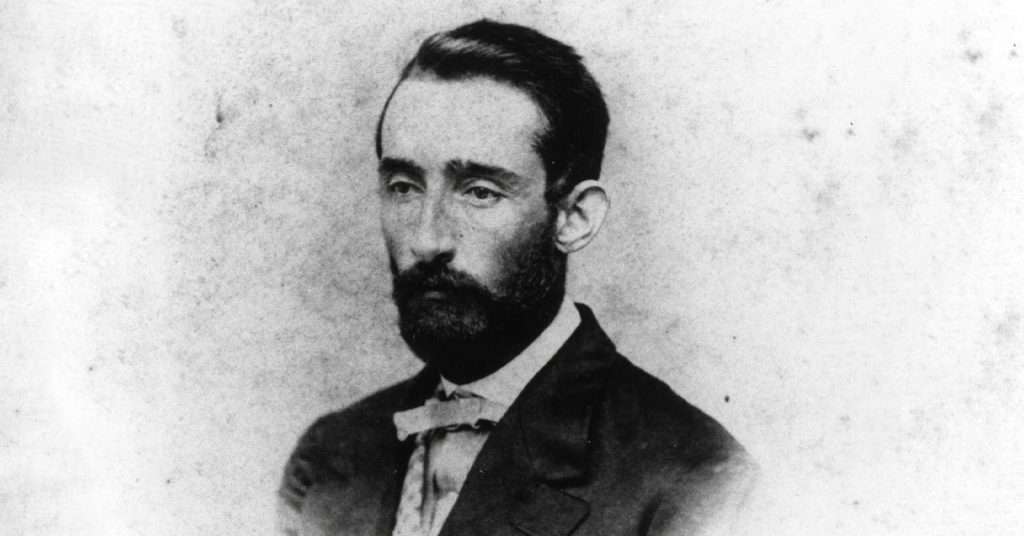

Wild Bill was born James Butler Hickok on May 27, 1837 in Troy Grove, Illinois. Despite the common perception of Hickok as a scoundrel even early on, he and his family worked to assist escaped slaves before the Civil War. The family home even had a hidden cellar which they would use to hide the escapees. When the Civil War began in 1861, Hickok joined the fray as a Union soldier and spy, even fighting in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. It was during this time that Wild Bill got his nickname. There are a variety of accounts of just how Wild Bill got his name, ranging from a nickname earned by a woman after standing up for a man or a name given from a resident of Rolla, Missouri. While the exact origin is not known, we do know that it is during this time that Hickok started using the moniker.

As the war went on, Hickok continued his service spying for the Union army and doing police work. Once the Civil War had ended and Wild Bill was without work, Hickok found himself spending time in Springfield, Missouri, leading to a moment that would make history.

A Duel on Park Central Square

Springfield made its place in the history books with a dispute between Wild Bill Hickok and Davis K. Tutt. Hickok was fresh off of his tenure as a Union scout and spy, playing poker on the night of July 20th, 1865 at the Lyon House Hotel on South Street. Tutt and Hickok were both frequent purveyors of the local gambling establishments and some have alleged that they had disputes before the gambling began. Some accounts say that the two were fighting over women or Civil War loyalties, as Tutt had previously fought for the Confederacy.

On this particular night, Hickok was on a winning streak. Tutt, angered from the fight and wanting to argue, claimed that Hickok owed him money from a previous gambling venture. The argument escalated until Tutt made a fatal mistake and took Hickok’s prized gold pocket watch as collateral for the so-called debt. Hickok asked for the watch back, only for Tutt to reply that he planned to wear the watch publicly in the town square the next day. Hickok advised Tutt against doing so “unless dead men can walk.”

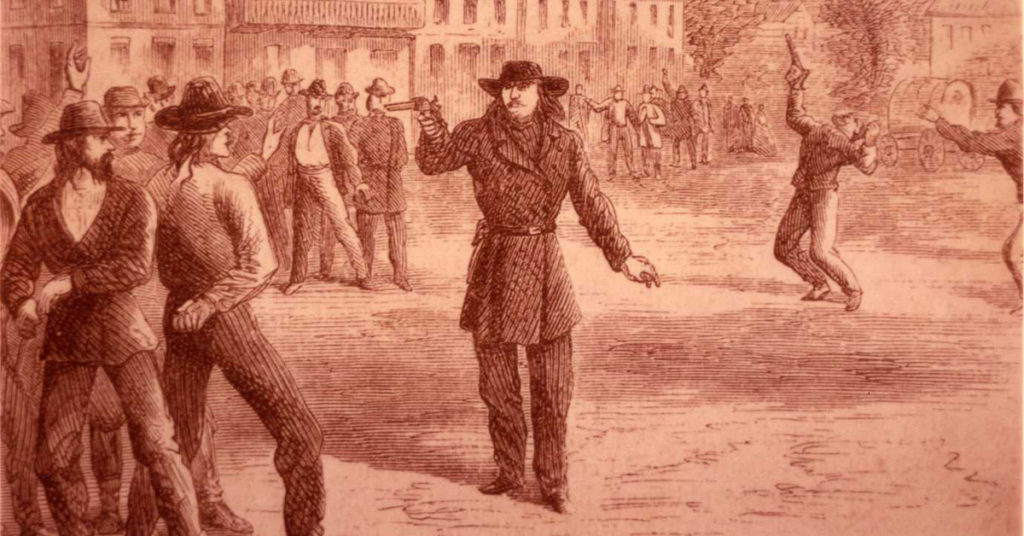

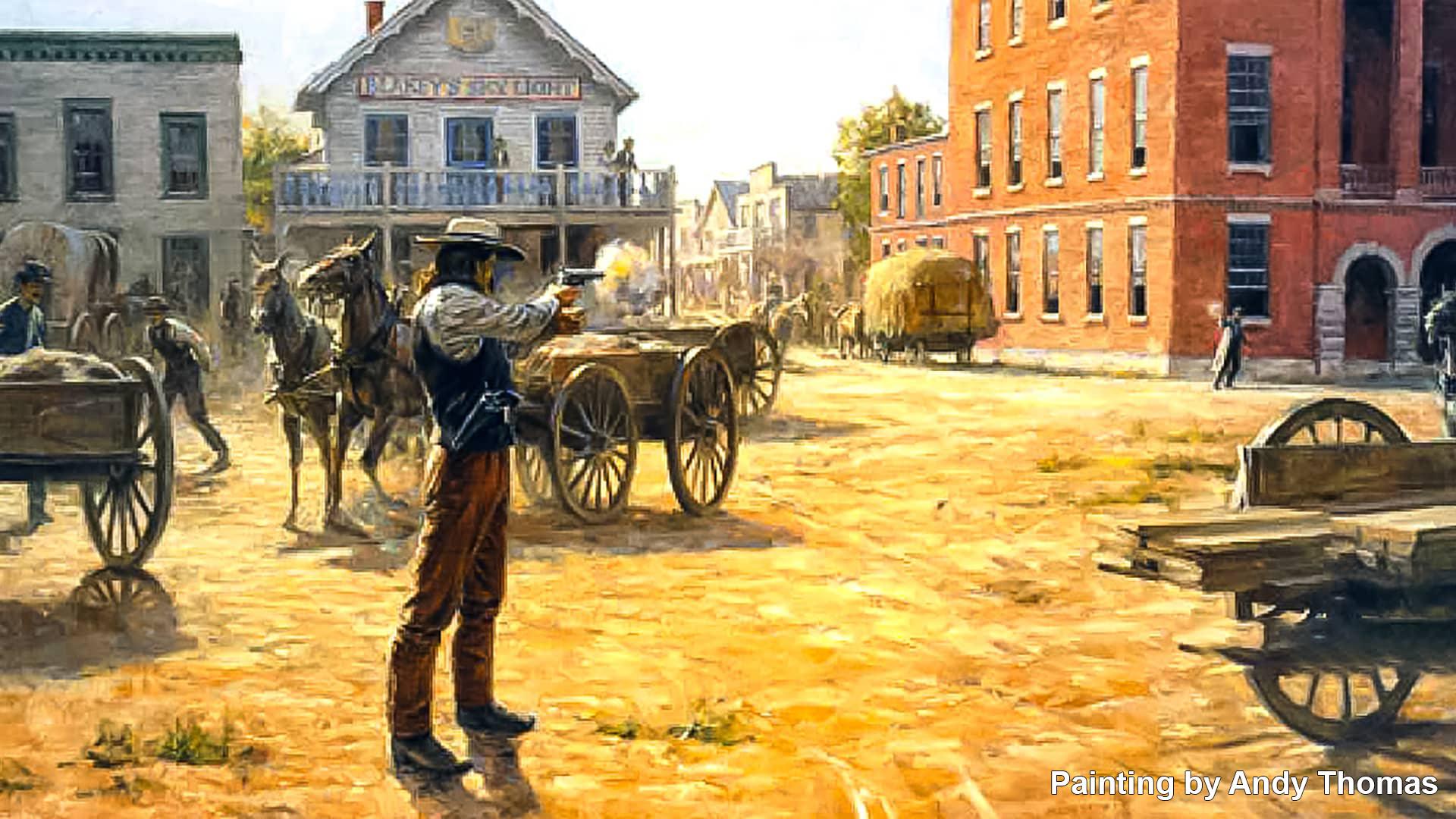

The next day, word reached Hickok that Tutt would be entering the square that afternoon wearing the watch. Hickok entered the square from South Street and soon after Tutt strolled in from Baker Alley in the northwest corner. At a distance of around 75 yards both men stopped and faced each other. Witnesses said that Tutt drew first and Hickok then raised his pistol and braced it over his arm and fired hitting Tutt in the chest. Tutt called out, “boys I am killed” before falling dead on the courthouse steps.

There was a three-day long trial held after Wild Bill made his deadly shot, where a jury ultimately decided that Hickok was not guilty of manslaughter due to the conditions surrounding the duel- namely, being provoked by the theft of the treasured pocket watch.

Life After Tutt

In the years that followed, Hickok found his passion working somewhat unsuccessfully in law enforcement. He ran for City Marshall of Springfield later but ultimately lost. He returned to the army briefly before coming back and becoming sheriff of Hays City, Kansas in the summer of 1869. A few months into his appointment as sheriff, he had already killed two men in the line of duty. This didn’t sit well with the residents of the town and Hickok lost re-election that November. His final stint in law enforcement was as marshal of Abilene, Texas, a job which he kept until the end of the cattle trade in Abilene led to the end of Hickok’s expensive tenure as marshal. In 1876, Hickok bid goodbye to his wife, Agnes Thatcher, and left for Deadwood, South Dakota in pursuit of gold. This would be the last time he would ever see his wife.

On his final night alive, Hickok was playing poker in a saloon. Usually a man to sit with his back to the wall, the only seat available this night was one where he was left exposed and unable to see behind him. A man by the name of Jack McCall, upset with Wild Bill from either a previous gambling debt or for allegedly killing his brother, came into the saloon and drew his pistol. He shot Hickok in the back of the head, murdering him in front of the entire saloon. As Hickok died, he was holding a hand of two black aces and two black eights, a card pairing that is now known as the “dead man’s hand.”

McCall was arrested and brought to trial for the murder, only to be found not guilty. Unfortunately for McCall, he was tried again for the crime, avoiding double jeopardy since the verdict came from Indian country, making it invalid in the American courts. In his second trial, McCall was found guilty and later hanged.

For more information about the life of the sharpshooter that helped put Springfield on the map, join us at the opening of the Wild Bill Hickok and the American West gallery on the 2nd floor of our new reimagined History Museum on the Square in 2018.